What do you uniquely offer that people desperately want?

That’s the critical question that founders must answer to achieve product-market fit. In fact, Andy Rachleff, who co-founded Benchmark and first coined this term, summarized his entire entrepreneurship course at Stanford as answering that one question.

Product-market fit is the most important milestone for an early-stage startup. Without it, you can’t start scaling your business efficiently. Once you achieve the first wave of product-market fit, hitting your business goals will be easier. Customers will refer new prospects to you, and your unit economics (LTV/CAC) will be strong. Webflow Co-founder Bryant Chou recalls in this interview on the Startup Field Guide podcast, “Once the market understood what we could do, it was just, we want more! We want more templates, more functionality, more tutorials. Our product development velocity was our marketing strategy for organic growth.”

Founders have been asking the same questions for years — how do you find product-market fit? How do you measure it, and how do you know if your startup has achieved product-market fit? — and while much has been written on the subject, there’s no shortage of misconceptions. To debunk these myths, we interviewed Andy about the counterintuitive secrets behind product-market fit on the Startup Field Guide podcast.

Andy Rachleff is an iconic Silicon Valley investor with an incredibly accomplished career in the tech industry. He co-founded Benchmark Capital in 1995, which quickly became a leading fund with investments in world-class startups like eBay, Twitter, and Uber. In 2008, Andy started Wealthfront, which has mainstreamed robo-investing and now manages more than $20 billion for half a million customers. More personally, Andy has been a tremendous mentor to us at Unusual Ventures.

Product-market fit occurs when a company addresses a good market (large, monetizable) with a differentiated product (unique, compelling) that can satisfy a specific market segment’s needs. The target customers are buying, using, and telling enough people about the company’s product to sustain its growth efficiently. After this point the company might choose to build new products for which they need to find product-market fit again. If successful repeatedly, they can build a massive multi-product business that lasts generations.

However, before you start building anything, there are some must-have ingredients that your startup needs for it to have a shot at finding product-market fit.

No company has found product-market fit without a unique insight that their founding team either had from inception or discovered while working on a previous idea and then pivoted to. Unique insights usually occur when there is massive change happening to a market and/or a technology framework. “Without change, there’s seldom opportunity,” says Andy.

The nature of insights varies. A startup might identify a market need that incumbents have ignored because it’s an unattractive segment to them. A great example is Canva’s focus on 40 million amateur, collaborative graphic designers while Adobe focused on professionals.

Others might identify a new technology that enables workflows not possible or performant before. Figma’s success with WebGL to build a multiplayer UI design platform is a great example of a technical insight meeting an overlooked and growing market.

For Vanta CEO Christina Cacciopo, the insight was a big shift in market demand for SOC2 compliance in 2018. “When we talked about helping with compliance, even startup CTOs would introduce us to their engineers immediately,” she said. Vanta immediately pivoted their product focus from security to compliance.

Whatever your unique insight might be, it needs to answer these investor questions: why now and why you?

Andy states that founders can not succeed solely due to grit or leadership skills. “I think entrepreneurs succeed because they have a unique and powerful insight that leads to a product that people desperately want.”

“I think entrepreneurs succeed because they have a unique and powerful insight that leads to a product that people desperately want.”

— Andy Rachleff

How else, he says, can you explain a 25-year-old running a billion-dollar business? “They’re not great executives yet, they happen to have great insight.”

For customers to first pay attention to a new idea that no one in their network is talking about yet, it needs to be radically different from the status quo. This is why your product vision can’t be simply incrementally better than well established incumbents.

“If you’re just going to add incremental improvements to your product, it’s unlikely people are interested, because there’s a good enough alternative they already use,” says Andy.

When Snyk launched its security startup in 2015, it was in a very crowded space. However, it had a radically different approach to the problem than any existing company. Instead of focusing on CISOs and selling top-down, Snyk focused on developers and sold bottom-up. “The shift-left in DevOps was our eureka moment. We saw that security needs to come along for this ride,” said Snyk Co-founder Guy Podjarny.

For customers to risk or invest their time in adopting a brand-new startup’s product to satisfy a critical need, they need to be desperate. Investors also call this the “hair on fire” problem.

Desperation can manifest in many different ways. It can stem from boredom and frustration with existing tools or from a complete absence of choices preventing potential customers from taking any action at all.

When Henry Ward started Carta in 2012, he recalls that it was difficult to get founders and lawyers to switch to their cap table management software. While it was more convenient, it was risky to switch to a new pre–Series A startup for such a critical need. The company’s breakthrough came in 2014 when they started offering cheap, fast 409A valuations — something founders hated paying a lot for. The status quo was slow and expensive, giving Carta its desperate customer. “They all hated 409As,” says Henry.

Product-market fit doesn’t have one-size-fits-all metrics; in fact, how you measure it can differ a lot based on your business model and experiment design.

For a typical consumer business, Andy believes the best heuristic of success is whether the company can generate exponential organic growth in retained users — not paid growth in acquired users. You can always “fake” growth by spending more money on advertising and promotion. “The only way to generate organic growth is through word of mouth. And the only way you generate word of mouth is through delight,” Andy says.

Our advice for consumer companies is this: don’t spend any money on marketing until after you’ve proven exponential organic growth. In recent years, consumer and bottom-up product companies in private beta (and hence not growing yet) have been using a survey framework first proposed by Sean Ellis, co-author of Hacking Growth, that asks active users how upset they would be to lose access to the product. Over 40% of users at scale being upset indicates you have a sufficiently unique and compelling product that wouldn’t be easy for them to replace.

On the enterprise side, if you have a top-down sales motion, a good metric for product-market fit is hitting a sales yield of greater than one with a repeatable playbook. Mark Leslie, Co-founder of Veritas, who coined the term “sales yield” in his famous paper on the sales learning curve, defined it as the ratio between your annual net revenue and the fully loaded cost of your sales team. To hit a sales yield of greater than one, customers must be buying the product to solve the same set of problems; and a sales team (not the founder) can generate a gross margin on products sold that exceeds the sales team’s costs in the same period — which is hard to do.

“You need to find a desperate customer who understands your product’s value proposition even if pitched by a newly hired salesperson,” Andy says. Until you reach a sales yield greater than one, you’re still in customer discovery mode and the founder/CEO should be selling.

To reach product-market fit, Andy urges founders to test the three parts of their company strategy that constitute a business:

The value hypothesis represents the what, the who, and the how:

The value hypothesis states the primary reason why a specific set of target customers might want to use your product. It is obviously important to find out whether people really want to solve the problem that you intend to fix. “You can look at search results, do a Kickstarter, or a smoke test where you run an advertisement for the product, to see if anybody might be interested in it,” he says. For enterprise software, companies trying to build their own solutions to the problem is a good indicator that fixing it is a priority for them. They need to have already spent money or time trying to solve that problem themselves.

In doing your research, remember: just because people say they’re interested in solving a problem doesn’t mean they’ll use what you intend to build. This brings us to the implementation. In order for someone to use your product, your approach to implementing a solution to their problem must fully resonate with them.

Keep in mind that a response of yes or no is better than maybe. “A maybe is hard because it’s basically a no with false hope,” Andy says.

Arctic Wolf Founder-CEO Brian NeSmith believes maybes are worthless. If you ask a customer if they’re interested in your product and they say, “Maybe if you had x features, I’ll buy,” they’re not desperate, and might never buy your product. They might just be avoiding saying no.

Andy suggests digging into the maybes. Case in point: when Andy heard maybes from early potential customers at Wealthfront, he’d follow up with “why not?” to encourage honest feedback. At the risk of annoying early potential customers, it’s important to keep digging for the truth. Andy says he would rather annoy 100 early potential customers than risk not reaching a potential market of 10 million customers with the right product.

This brings us to the growth hypothesis. Once you have validated a unique insight and an implementation that works for your customers, you must find the right way to reach them repeatedly at scale. How do you cost-effectively acquire customers? The growth hypothesis represents the assumptions around how new users will find and start using your product, and how the company will grow.

Startups often make the mistake of only pursuing “lighthouse” accounts — famous people or brands to reference their product out of the gate. The problem, Andy says, is buyers at lighthouse accounts are usually pragmatists; they need to be somewhat risk averse. The result becomes a catch-22 — you’ll try to sell to someone who isn’t really going to buy until you have references.

Serial entrepreneur and Unusual Ventures Co-founder Jyoti Bansal is a big believer in cold calling before building anything. “I like to have a minimum of 50 conversations with small to mid- sized prospects via cold outreach,” he says. Having built two unicorns in enterprise software, Jyoti has realized that investors’ warm intros to massive customers are a waste of time — they simply don’t have urgency to change what they are doing.

Enterprise startups might assume they should go after big logos in a big market from the get-go, but Andy suggests the opposite. For enterprise brands, the better, counterintuitive approach is to sell to small- and mid-sized companies that are willing to take more risk and are desperate for your product.

For instance, in its early days Jyoti’s startup Harness, a CI/CD platform for software development, exclusively focused on teams kicking off new Kubernetes projects. As you build out the whole product — all the interfaces, additional features, and the support from third parties needed to solve the problems to get the references — you can go after the pragmatists.

“The counterintuitive thing is that you should not go after the big market first. It’s the exact opposite of what everyone tells you.” — Andy Rachleff

“Now, if the ultimate size of market addressed is the single greatest determinant of the outcome, then of course you should go after customers in those big markets to test your value hypothesis,” Andy adds, noting that the problem is that markets adopt products in a particular order.

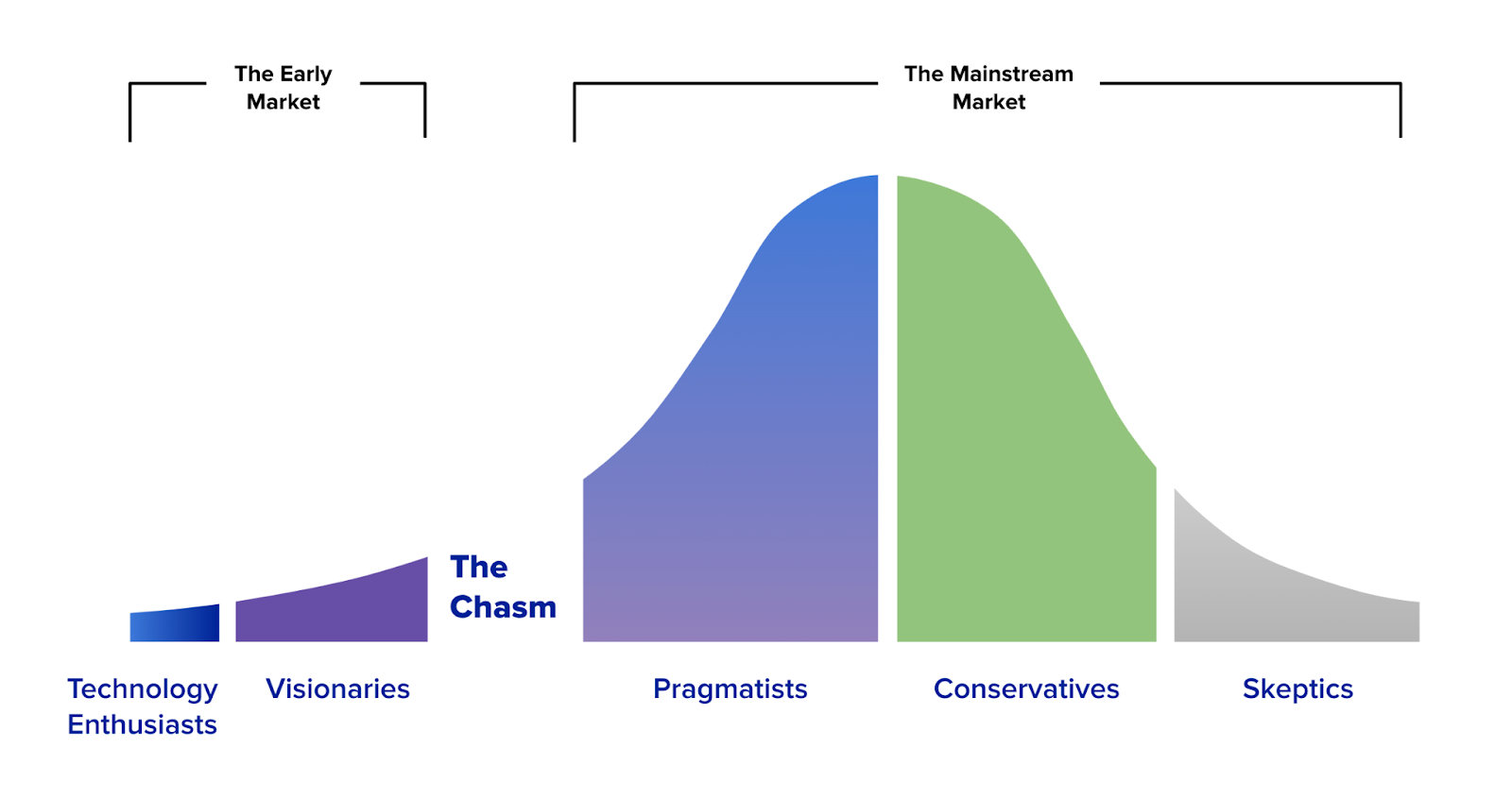

In Crossing the Chasm, author Geoffrey Moore explains that for every product, there are four main types of customers who adopt new products: innovators, early adopters, early majority, and the late majority. The fifth, laggards never switch. Innovators always present a smaller market opportunity but are the most likely to adopt.

Startups can all too easily get caught in the trap of tweaking their product instead of focusing on the more important issue: identifying the customer they’re creating a unique product for.

Imagine you have a directional idea, an insight around a problem that you have deep conviction in. You still might not be sure what the correct implementation (product) of the solution to this problem is. Let’s call this “the what.” It’s tempting to pick a customer and start building the solution based on what they are asking for (which might not result in a unique product at all) as opposed to defining a clear hypothesis for your implementation of a unique insight and identifying who is excited to use it.

Now, many startups instinctively iterate on the product by adding features to get someone to buy, but that almost never works. If your initial value hypothesis does not prove to be correct, don’t add more features — that doesn’t turn someone into a desperate customer. “You have to change the audience to whom you target the product, to try to find a common audience that’s desperate for what you do,” Andy says. “And that’s why iterating on the who, rather than the what is almost always the right thing to do.”

“You have to change the audience to whom you target the product, to try to find who is desperate for what you do.”

— Andy Rachleff

Edith Harbaugh, the co-founder of Launch Darkly, a feature management platform, recalls how they iterated on the who: “We discovered that Silicon Valley companies were just not good customers for us because they were more likely to have built an in-house solution for the problem we solved.” Instead of trying to build a more advanced solution for these companies, Edith pivoted to focus on companies outside Silicon Valley that were short on engineering talent and desperate for a solution they could just buy.

Don’t go after the growth hypothesis until you’ve proven the value hypothesis. “If you don’t lay a strong foundation — if the dogs don’t want to eat the dog food — it doesn’t matter how cost-effectively you can acquire customers. They’re not going to stay and it’s not going to be effective,” Andy says. “Almost no one’s initial value hypothesis is correct. And that’s true for every successful company.”

“Almost no one’s initial value hypothesis is correct. And that’s true for every successful company.”

— Andy Rachleff

What we don’t realize is that successful companies often revise their value hypothesis in order to get it right. Once they succeed, however, they revise history as well. As consumers, we like simple stories and prefer to buy from companies that always intended to serve our needs.

For Nextdoor Co-founder Sarah Leary, the company’s breakthrough insight came from searching for offline communities and was not immediate. Before they built Nextdoor, the team spent 2.5 years building Fanbase, an online community for sport enthusiasts. While it scaled to 15M page views, people didn’t come back. Their first value hypothesis was wrong. They then pivoted to the idea behind what eventually became Nextdoor. The team decided to focus on proving their value hypothesis through rigorous user research. Sarah recalls that their engineers “didn’t write a single line of code” for the first few months because the entire company was focused on validating their early assumptions by talking to potential users who would eventually become their early adopters.

Achieving product-market fit is not a one-time event. If you slow down or stop innovating on your core product, you might no longer be uniquely compelling. Other companies will start to match or outperform your product and customers will start to churn. Your business metrics will weaken. It is also important to approach each new product you launch with the same lens you took to your first and look for what you can do uniquely for desperate customers.

Unusual Ventures is an early-stage fund dedicated to helping founders accelerate their path to product-market fit. Learn more about every aspect of the PMF journey with these resources:

The Unusual Field Guide, a comprehensive tactical guide for founders just getting started.

What are design partners and Iterating to MVP with design partners

Guide to raising Seed and Series A

Our companion podcast, featuring guests who have built iconic unicorns like Carta, Snyk, Harness, Webflow as well as:

Curtis Liu, co-founder of Amplitude

Guillermo Rauch, co-founder of Vercel

Arvind Jain, co-founder of Glean

Want more advice to achieve product-market fit? Sign up for the Unusual Ventures newsletter for monthly tips, access to events, and more.